Co-Creating the Great Value of Engagement for Individuals and Organizations

Rikard Larsson, Katarina Kling, Raj Bowen, Chris Hardy, Uliana Morokhovska, K Sudarshan, and Morgan Wee

There is hardly any single factor that is more valuable for both individuals and organizations than engagement (Larsson & Kling, 2017). The purpose of this article is to (1) summarize practical and academic research findings about the value of employee engagement; (2) highlight what makes engagement so valuable; and (3) outline a practical approach for how we can co-create more engagement for the mutual benefit of individuals and organizations.

1. How valuable is employee engagement?

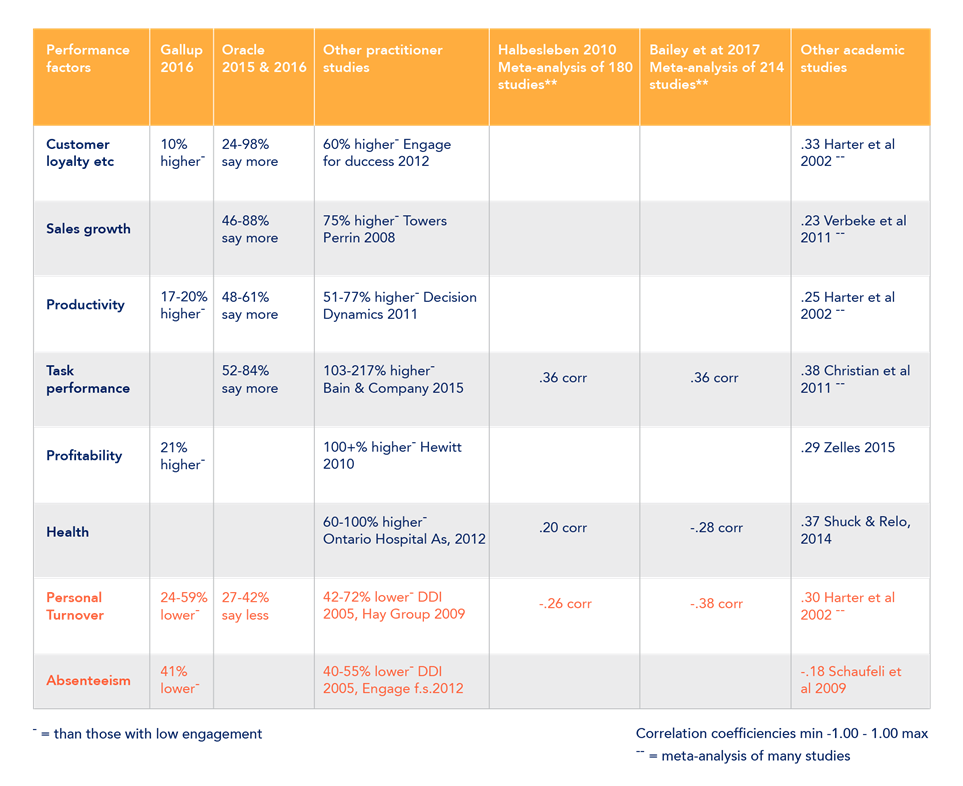

Even though it is a relatively new research area (Macey & Schneider, 2008), both practical and academic research largely agree on the many individual and very many organizational benefits of higher employee engagement. Examples of the findings of practical engagement research are displayed to the left and the findings of academic engagement research are shown to the right in Table 1 below.

Note that all the significant findings are positively related to beneficial outcomes and negatively related to bad outcomes. This means that employee engagement clearly helps us and our organizations with both more good effects and fewer bad effects.

Most of the practical findings compare how much better high-engagement individuals, teams, units, and/or organizations are compared with those with low engagement in terms of 10-217% higher customer loyalty, sales growth, productivity, task performance, profitability, and health as well as 24-72% lower personnel turnover and absenteeism.

Most of the academic studies report statistically significant positive correlation coefficients with the beneficial outcomes and negative correlation coefficients with the costly outcomes. There have now been so many existing academic articles that several of the displayed studies above are meta-analyses of as many as 100 – 200+ previous scientific studies each (Harter et al, 2002; Halbesleben 2010; Christian et al, 2011; Verbeke et al, 2011; and Bailey et al, 2017) and thereby represent very powerful summaries of a great deal of academic research.

Several academic reviews of engagement research point to the lack of consensus in how engagement is conceptualized and measured (e.g., Macey & Schneider, 2008; Bailey et al, 2017). Normally, such conceptual and measurement confusion create so much information noise that it is hard for a relatively new research area to find consistent empirical results.

Here, we see that engagement research with practical as well as academic purposes using different conceptualizations and measurements still arrive at very consistent and strong empirical findings. What makes engagement research so empirically powerful in spite of not yet having overcome its “noisy” theoretical and methodological aspects?

2. What makes engagement create so much value?

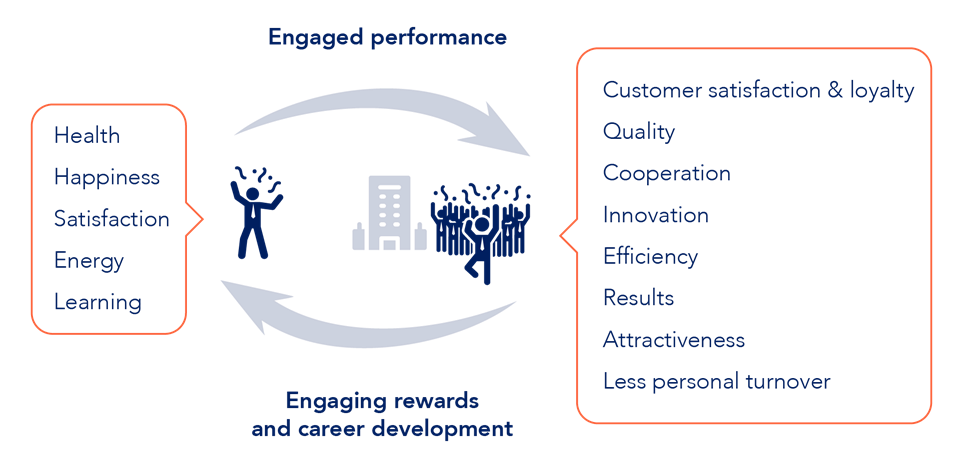

Prior to the current engagement focus, most organizations were assessing employee satisfaction, motivation, commitment and so forth. These assessments were mainly about what individuals get for and feel about their work. It is important to observe that engagement is not simply a new label on these old bottles. Instead engagement adds at least three key both/and characteristics as illustrated in Figure 1 below (inspired by Barnard, 1938; Simon, 1948; and many others).

First, engagement adds the organizational dimension to the previous individual focus. Second, engagement also adds what the individuals give to their organizations and not only what they get from their organizations. Third, engagement adds the key component of how competent these individual contributions to the organization are beyond the motivation of the people.

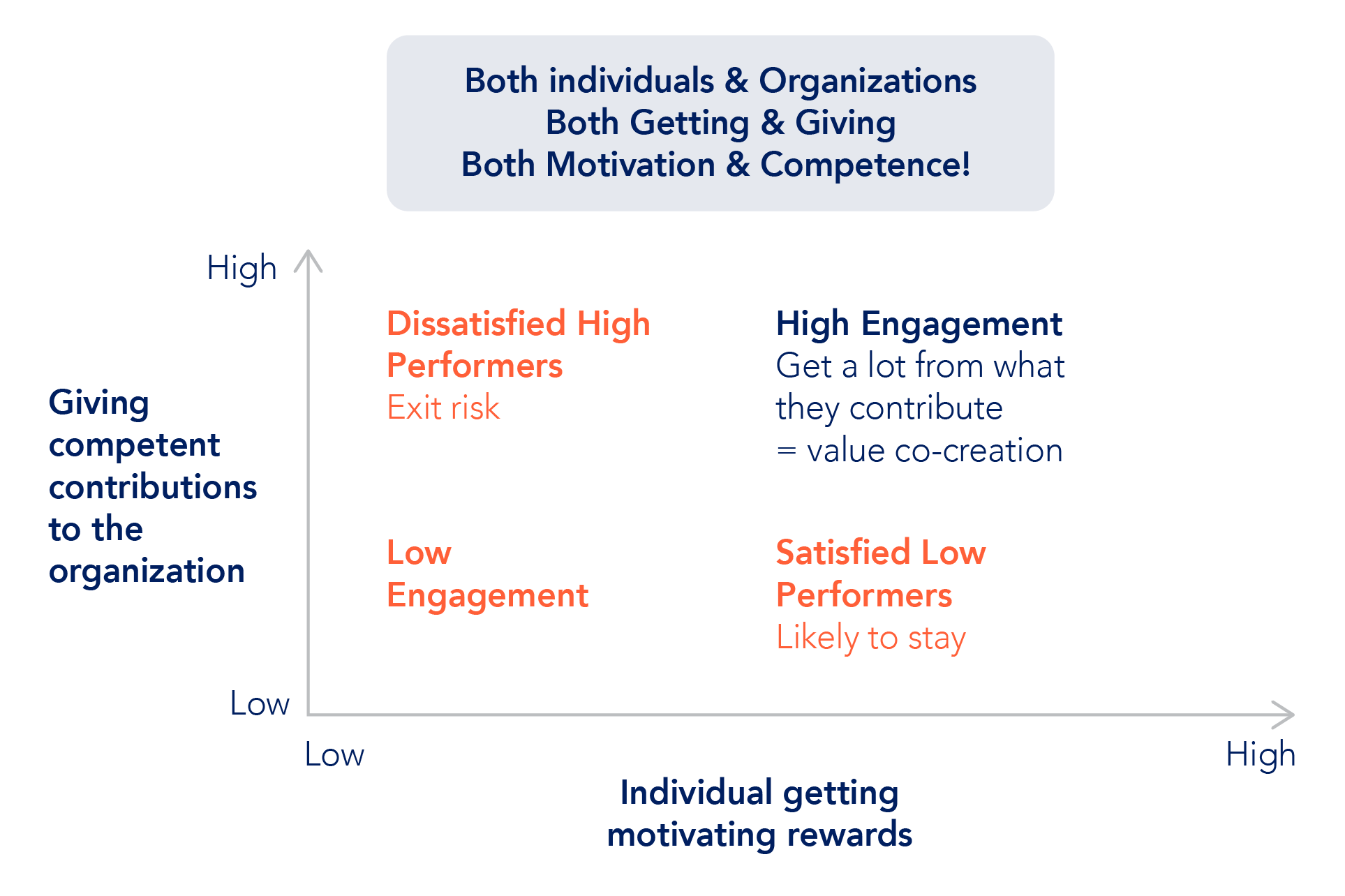

When both dimensions of Figure 1 are low, then we have the clearest cases of low engagement or high disengagement. However, some of those individuals who are getting motivating rewards can to some extent be satisfied stayers that perform less well (bottom right-hand corner). In contrast, those who perform well with good contributions to their organization can instead to some extent be dissatisfied from not getting sufficiently motivating rewards and therefore may choose to exit (upper left-hand corner).

The strongest engagement is found when both dimensions are high. While the satisfied low performers stay for what they get, the highly engaged stay mainly for what they are enabled to contribute! This highlights how engagement and value co-creation increase more along the diagonal in Figure 1 and that they are more both/and-concepts that are more needed in an increasingly both/and-world.

3. How can we co-create more engagement?

Given that engagement is largely co-created, the most powerful ways to increase it center around improving how individuals & organization and motivation & competence dynamically meet in our working lives. This includes overcoming two of the most difficult barriers and greatest opportunities of engagement (Larsson & Kling, 2017):

- Individuals have different drivers & killers of their engagement; and

- Engagement is dynamic and never “fixed once and for all”.

There are hardly any general engagement panaceas, since what can be an engagement driver for some persons can be an engagement killer for some others. This is both a complicating barrier to achieving greater engagement and fantastic sources of engaging diversity that helps us to deal with today’s growing complexity.

Nor are engagement solutions permanent. Both individuals and organizational situations change more or less all the time. What once was engaging for some people can become disengaging to them over time, while other engagement drivers can evolve. Engagement is always a work in progress and if left untended, it tends rather to deteriorate. At the same time, it is these dynamics of engagement that empower us to learn, develop, and lead today’s accelerating change.

Individuals and organizations meet dynamically in the concept of careers. Traditionally, individuals are viewed as parts of their organization. This is beautifully balanced by organizations actually becoming parts of individuals’ careers over time. The relevance of this career perspective is growing by the day as we tend to change organizations more frequently during our working lives.

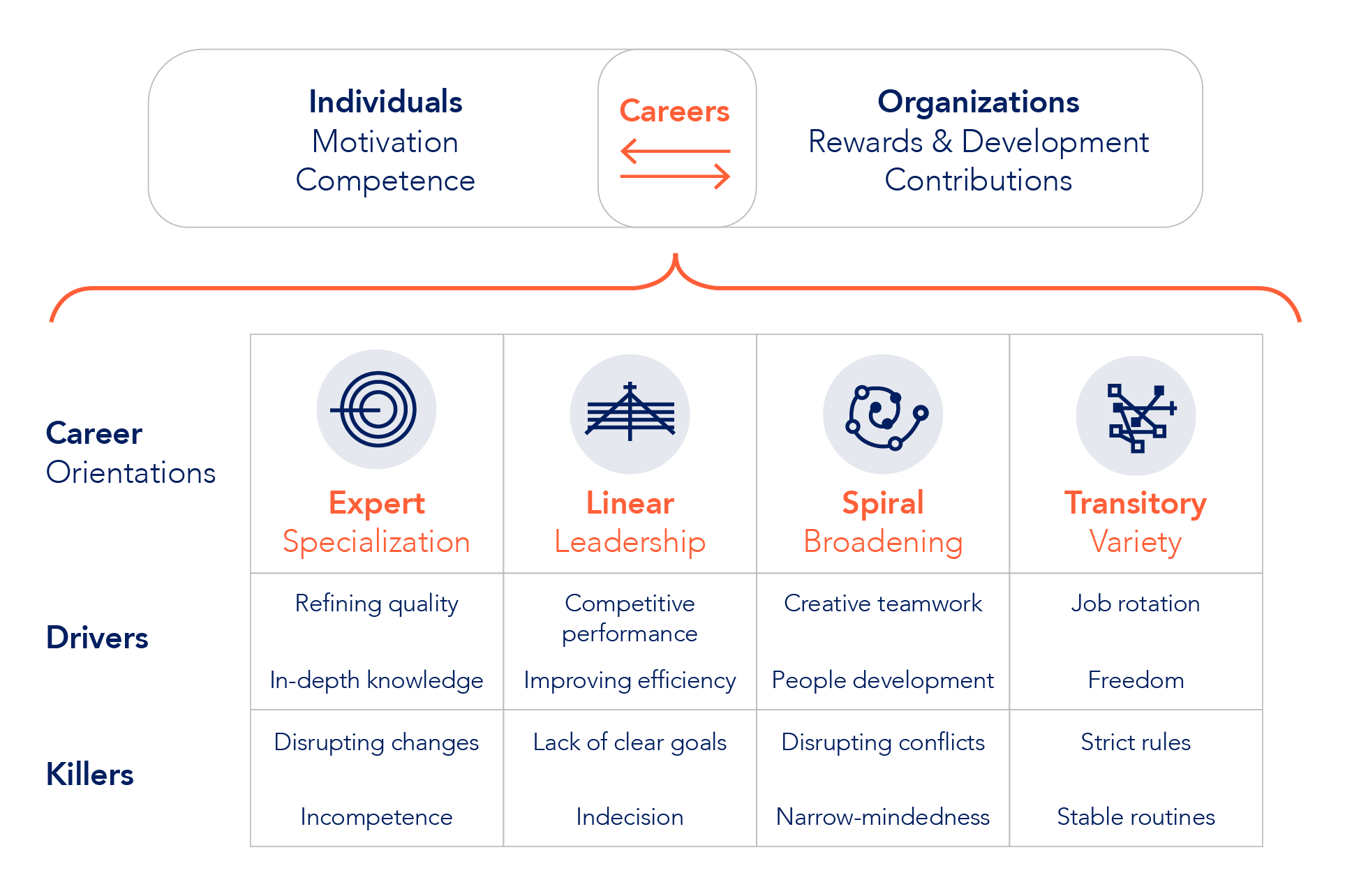

Decision Dynamics Career Model™ is one of the world’s leading career models in research and practice (e.g., Driver, 1979; Von Glinow et al, 1983; Brousseau et al 1996; Larsson et al, 2007; Larsson et al, 2020a). It distinguishes between four different career concepts and sets of career motives that are powerful in capturing relevant similarities and differences between persons’ various engagement drivers & killers as illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The Expert career orientation is aimed at long-term specialization to become as good as possible in a chosen professional area for as long as possible. Experts are their careers by identifying themselves with their professional choices, such as I am an engineer, or I am a teacher.

In contrast, Linears make their careers by climbing up the organizational ladder to higher managerial positions with greater responsibilities as fast as possible.

Spirals instead discover their careers by finding new related jobs where they can both utilize and broaden their experiences in lateral and often creative ways every 5 – 10 years.

Finally, Transitories may think that they do not even have any careers, since they tend to switch between as different jobs as possible as often as possible. This has historically not been seen as a proper career, but rather as “jack of all trades, master of none”.

These four fundamental career orientations differ greatly in what engages versus disengages them the most, that is, their various engagement drivers & killers (Larsson & Kling, 2017). For example, Experts become doubly engaged by moving from for them killing changes towards more stable high-quality specialization. At the same time, they would become doubly disengaged by moving in the opposite direction from their favorite long-term focus towards hasty changes that they hate. Compare this with Transitories who love more changes, while being disengaged by being “stuck in the same old rut.”

If we know our own and others’ main engagement drivers & killers, we could co-create so much more engagement. Perhaps the biggest barrier to more engagement is that most of us do not even know our own main drivers & killers. Our research has shown that only around 40% of us are striving for the career development that would engage us the most (Larsson et al, 2016). There are also indications that we only guess 20-30% correctly about our managers’, co-workers’, and direct reports’ main drivers & killers.

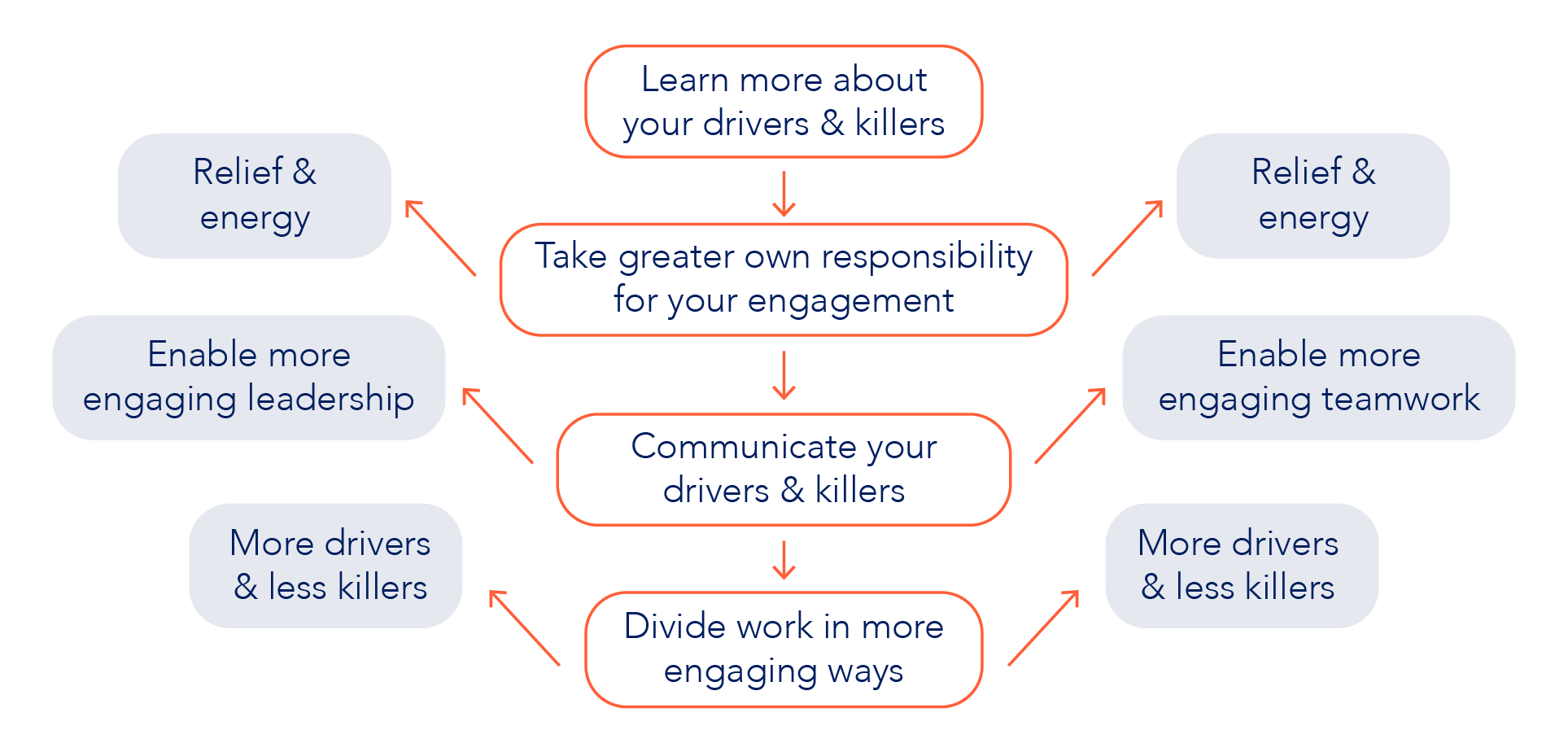

This very common lack of knowledge of our own and others’ drivers & killers severely limits how much engagement we can co-create. However, managers and co-workers can gain knowledge of their own primary engagement drivers and share this information with relevant others by answering a short questionnaire, learning a little more about the Decision Dynamics Career Model, reading one's own personal Career Report, and communicating one's results to respective managers and co-workers as illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Together, we can co-create virtuous rings of engagement by having our managers and co-workers:

1. Learn more about their primary drivers & killers from doing their Career Reports.

2. This enables each of them to take greater own responsibility for their engagement and thereby providing relief and energy to already busy managers and co-workers who often guess wrong about what engages one another most.

3. The better knowledge of their drivers & killers can also be easily communicated to their respective manager to enable more engaging leadership as well as to their closest co-workers to enable more engaging teamwork.

4. The shared knowledge of their drivers & killers also enables them to divide different work activities in more engaging ways where they can trade some of their killers for more of their drivers.

These steps have been utilized in various customized cases with great success, such as the leading Scandinavian bank, Swedish Armed Forces, and the greatest white-collar union in the Nordics (see Larsson et al, 2016). For example, some of the benefits achieved by the bank include all-time high motivation index improvement, more attractive employer branding, and less personnel turnover (Larsson et al, 2020b).

This article is addressed to everybody throughout organizations from the CEO and Chairperson to all individual contributors. The more people who discover the great value of engagement, the more such values we can co-create together. Please share it in your organizations and contact us to help you to boost your co-created engagement.

Co-authored by Rikard Larsson, Katarina Kling, Raj Bowen, Chris Hardy, Uliana Morokhovska, K Sudarshan, and Morgan Wee

Decision Dynamics (Sweden) and EMA Partners (India, South Africa, Ukraine & Singapore)

rikard.larsson@decisiondynamics.se; katarina.kling@decisiondynamics.se; r.bowen@ema-partners.com; c.hardy@ema-partners.com; u.morokhavska@ema-partners.com; k.sudarshan@ema-partners.com; m.wee@ema-partners.com

Insights

Our Insights are the research and leadership trends that will benefit both clients and candidates, and inspire them to become better professionals